Music and the Geometry of Time Dilation

- Huck Hodge

- 3 days ago

- 20 min read

Updated: 1 day ago

HUCK HODGE

One big difference between Newtonian mechanics and the special theory of relativity (STR) involves the relativity of space and time. Newton, and Galileo before him, held that space and time are absolute. There is a single ‘now’ throughout the entire universe. This is intuitive: regardless of how fast I may travel relative to you, no matter where we are in the universe, it stands to reason that there is one uniform time for both of us; we can both agree, in principle, on what time it is. We might disagree about a lot of other things, though – like which one of us is moving. Sitting on planet Earth we feel like we are at rest. In fact, we are traveling at about 67,000 mph as we orbit the sun. Similarly, if you are on a train – one of those hi-tech Japanese bullet trains, say – you can still juggle (assuming you know how to juggle) despite everything around you moving at hundreds of miles an hour from the point of view of someone standing outside the train. From your perspective, you and everything around you, are at rest – until you throw your juggling pins in the air, that is. This is because everything on the train is in the same inertial reference frame. In fact, from your viewpoint, the person outside the train whips past at hundreds of miles per hour.

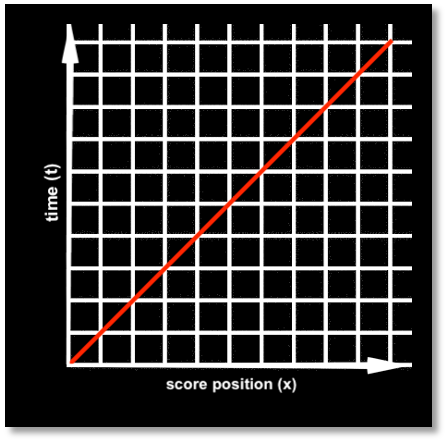

What if we want to chart your speed relative to that person outside the train? One way to do this would be to plot their path in space and time relative to yours on a graph (left side). Relative to the person outside the train, you (red line) are moving at 300 mph – to the east, let’s say. Your line reaches 300 miles on the horizontal axis (space) at just the point that it reaches 1 hour on the vertical axis (time). The stationary person’s line (blue) also reaches 1 hour on the time axis, but doesn’t budge on the space axis (they had nowhere to be for the last hour, I guess).

Now, relative to your own frame you feel like you are at rest, while the other person moves. So, what would the graph look like from your perspective (right side)? Your line is now vertical while the line of the onlooker moves 300 miles in the opposite direction. This kind of geometric rotation is known as a Galilean transformation. Here, space and time are constant, while velocity is relative.

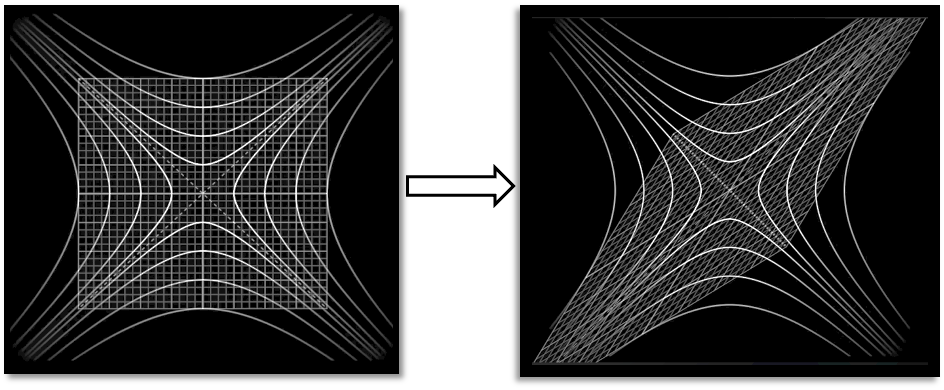

This is fine for speeds that are not significant fractions of lightspeed. But what happens as the train’s speed shifts from 300 mph to 300 million meters per second, the speed of light (c)? STR holds that c is invariant for everyone, no matter how fast they move, so a reversal in constancy vs. relativity of parameters sets in: the speed of light is constant, while space and time become relative. But if there is a constant speed in the universe, how could we chart the transformations between frames? After all, the train would be going the same speed in your frame and every frame outside the train. To keep this constant, we would have to twist space and time relative to lightspeed. This is called a Lorentz transformation, a hyperbolic swivel (called a velocity boost) between the space and time coordinates of different frames. Below we’ll chart light moving relative to a rest frame. Time units are set to seconds and space units are set to c. 3 x 10⁸ meters (1 lightsecond). Light propagates in all directions; since the graph reduces 3D space to a 1D continuum, the line rises to the right to show the light wave spreading in one direction over time, and to the left to show it spreading in the opposite direction.

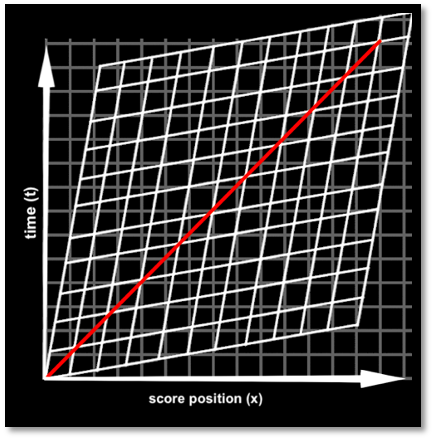

Let’s now boost the grid to chart its motion as it would travel relative to a faster velocity’s rest frame:

Coordinates shift for relative frames but the absolute speed of our light wave (and as we’ll see, the absolute distance of its lightspeed voyage) remains constant across frames. Notice how the lines still pass through the same 10 grid boxes, regardless of how “skewed” they are. In comparison to the unskewed grid, what had been distinct time and space domains are now smeared together:

One thing to clarify is that relativity is not “relational” all the way down. The speed of light in a vacuum is absolute: it’s invariant across all reference frames. But it’s also absolute in the sense that it is the maximum speed anything can travel relative to an observer. As a result, even though the coordinates of space and time may vary between reference frames, this doesn’t mean that there are no absolute distances. What it does mean is that distances are now going to be measured not in distinct intervals of space and time, but in units of a continuous spacetime. The absolute length of an object’s path in spacetime is called its proper time (𝜏). The object’s path is called its worldline. A worldline traces where and when the object exists, how it moves through space over time, and how it can causally interact within the limits set by the speed of light. The proper time of a world line will be the same across frames regardless of velocity, sort of like how an odometer measures the same distance traveled at any velocity.

Proper time is sometimes called process time because it corresponds to the unfolding of a process, be it the cycles of a clock, the burning of a candle, or a biological process like aging. In Newtonian mechanics, two identical processes should unfold at identical rates. Proper time units, the units used to measure the process, are tied to “clock” time (coordinate time) in every frame. Velocity should play no role in the unfolding of these processes. Two clocks should keep the same time even if one is stationary and the other is sent hurtling through space on a rocket. Coordinate time (t) is absolute in all frames and so proper time is always equal to it (𝜏 = t). But due to the invariance of lightspeed in STR, and therefore its constancy in all reference frames, the geometry splits proper time and coordinate time apart; the clock on the rocket will keep different (coordinate) time from the stationary one, even though their proper time remains the same.

A MUSICAL ANALOGY

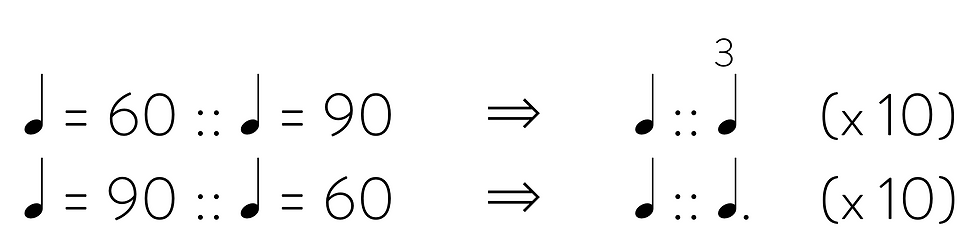

The idea that a process unfolds faster or slower depending on its velocity seems pretty strange. Perhaps one way to think about it is in a (rather loose) musical analogy. Whether or not it’s ultimately apt in a strict sense, this analogy may still sharpen our insights not just into time dilation, but into our thinking about music as well. Here goes: imagine several people playing a musical passage with a length of 10 quarter notes (q). Internal to any tempo frame, everyone plays q = 10. The passage really is 10 quarter notes long, regardless of the tempo it’s played at. This is its proper time. But in the time coordinates of each tempo frame, the passage is of different lengths relative to the other frames. From the point of view of a slower tempo, the passage is shorter (q > 10) when played at a faster tempo. From the point of view of a faster tempo, the passage is longer (q < 10) when played at a slower tempo, for instance:

We can push the musical analogy further, though as we’ll see, it starts to break down on close examination. Imagine now, like in the train example, that within each of these tempo frames, everything internal to a frame is “at rest.” It’s not clear what this would mean in our musical analogy, but we could perhaps think of it as a situation where, regardless of the tempo as it is observed externally from another frame, internally to each frame, the metronome still clicks at a rate matching a clock: 𝅘𝅥 = 60. Within each frame, the 10 quarter notes take 10 seconds to unfold. Each frame sees time flowing as normal within their frame, but time dilates or contracts when compared to the passage of time in other frames. Remember, from the point of view of the faster tempo, the slower tempo plays note values larger than quarter notes. So, 10 seconds in the faster tempo frame corresponds to more than 10 seconds in the slower frame. This is the basic principle behind time dilation.

We could plot this musical passage on a grid where the vertical axis shows time and the horizontal axis shows the position in the score (e.g., beats/measures, etc.). The notes are plotted in equal durational intervals up the t axis (𝚫t =1s; 1 note/s). On the x axis, they move to the right (𝚫x = 1 quarter note). This corresponds to beats at 𝅘𝅥 = 60 in this frame. Relative to this frame, a faster tempo would preserve the proper time of 10 quarter notes, but relative to the slower tempo it would stretch out in time, in this case by a Lorentz factor of 1.4. 10 seconds relative to the faster tempo’s rest frame corresponds to 14 seconds in the slower tempo’s rest frame.

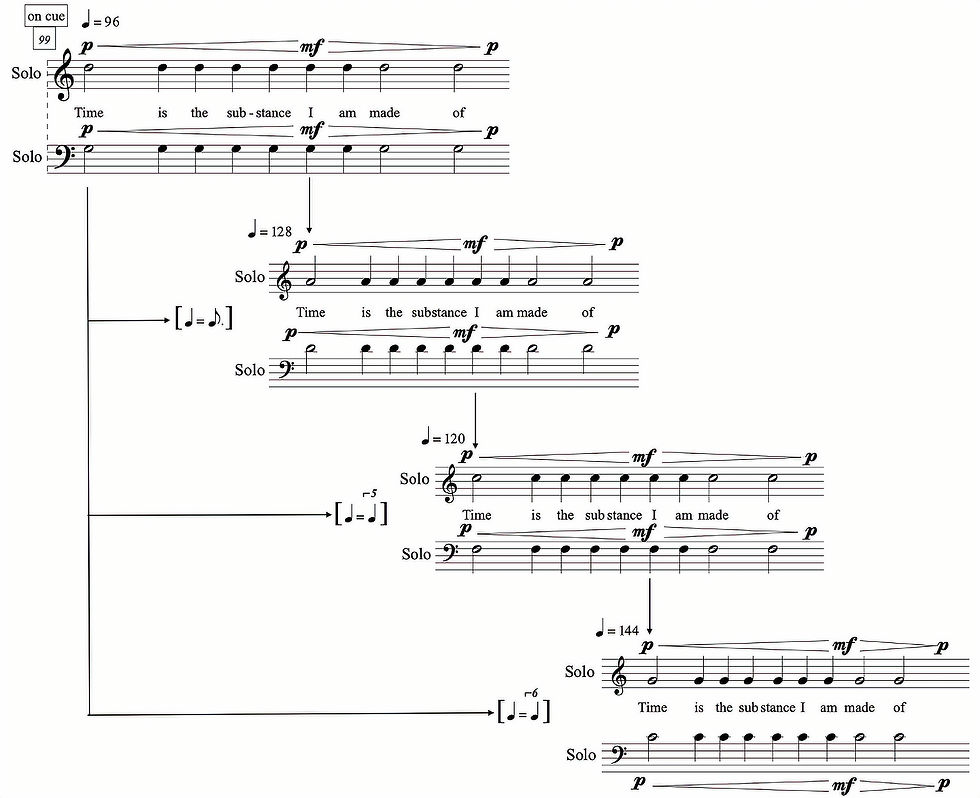

The following excerpt from my composition Time is the substance I am made of shows a similar setup in actual music. There are four tempo frames here, where the quarter note equals 96, 128, 120 and 144 BPM, respectively.

The proper time for each frame is 12 quarter notes. Each frame is “at rest” meaning that internally the tempo is set at 𝅘𝅥 = 60. Relative to Frame 1 (96 BPM) every other frame has shorter rhythmic durations (shown by the arrows branching from the first note). But relative to the other frames, the durations in Frame 1 stretch out. For example, relative to Frame 4 (144 BPM), quarters in Frame 1 dilate to dotted quarter-notes. You can get a very rough and inexact idea of how time dilation works here: imagine someone in Frame 1 who at the end of the passage jumps to Frame 4. Given that the durational ratio of Frame 4 to Frame 1 is 6:4, and since the passage takes 12 seconds internally to Frame 4 (remember time runs normally inside each frame), when they jump back to Frame 1 at the end of the passage in Frame 4, they will have found that 18 seconds have elapsed in Frame 1 {(12/4) x 6}. I want to emphasize that this is not the real equation for time dilation (for that see the coda at the end of this article), but the basic principle is roughly similar. However, it's worth spending some time looking at the ways this analogy fails.

For one thing, if we want to make it more precise, we would have to introduce a maximum tempo in our musical universe, a “musical speed of light.” This is not itself a problem with the analogy, the speed of light can be scaled arbitrarily. But it does show that our musical intuitions more closely align with Newtonian mechanics, which holds that there is, in principle, no limit on velocity. Why should there be an absolute, finite limit on tempo?

The bigger problem has to do with what it means for a tempo frame to be “at rest.” Between frames, tempo is functioning analogously to velocity: from the frame of a slower tempo, a faster tempo seems to have a higher “velocity.” But internally to each frame, the tempo is also functioning as a metric of the coordinate (“clock”) time. This forces a contradiction. In STR, a rest frame has zero velocity (it sees every other frame as moving, but not itself), and clock time runs normally: 1 second per second. But in the musical analogy, to keep clock time normal in a rest frame we had to set the tempo to 𝅘𝅥 = 60. But then this means that the velocity is also 𝅘𝅥 = 60, so it is not a rest frame after all. We can’t set the internal tempo both to 0 and 60 BPM at the same time, and so the analogy fails.

This might be what makes that part of the analogy so counterintuitive. How can music played in a faster tempo end up being longer in the time that a slower tempo experiences? Yet in STR, the relationship holds: processes unfolding at a higher velocity unfold more slowly relative to a rest frame. If you travel faster in space, you travel slower in time, relative to someone traveling at a lower velocity.

You can think of spacetime intervals as a continuum stretched between a space direction and a time direction. Sitting still, you are maximally in the time direction. You are “using up” spacetime intervals primarily with respect to their time portion. Traveling extremely fast through spacetime, however, your intervals are “used up” by more of the space portion. A worldline’s distance, its proper time, remains constant between frames, but the frames disagree on its precise mix of space and time values. From your rest frame, if you were to look on a graph expressed in familiar units like hours (t-axis/vertical) and miles (x-axis/horizontal), your line would be going up vertically along the time axis, with no motion on the space axis. But someone close to lightspeed would have a line that’s nearly horizontal, going along the space axis yet moving only slowly along your time axis. Obviously, this doesn’t make sense for music. There’s no way to increase duration in seconds of a passage relative to a slower tempo by playing it in a faster tempo. You can’t reduce the “time direction” of a musical passage by taking a longer or faster trip in the “score direction”.

In fact, there are reasons to doubt that score-position is consistently analogous to space at all. On a first approximation the analogy seems to fit. We “travel” through the score at a certain “velocity” (i.e., tempo) over time. If we vary the tempo, we will arrive at specific locations in the score (e.g., beat 3 of measure 47) earlier or later in time. Even our way of talking about tempo (beats per minute) distinguishes score-position from time, similarly to the way velocity distinguishes space from time (e.g., meters per second). Moreover, if we ask how long a piece is, a perfectly satisfactory, if overly granular answer would be “100 quarter notes.” This doesn’t tell us anything about how much time will have elapsed when we reach the end of the piece, and so it seems that score-position is an entirely different parameter from time.

What’s more, one can imagine a piece where players change direction in the score at arbitrary times. In certain pieces – Schoenberg’s table canon, for example – it is entirely coherent to play the piece backwards, and even upside-down, a dimension not available to time. All of this seems quite similar to space and quite different from time. Even if we imagine that one could travel backwards in time, doing so entails numerous logical paradoxes that do not come about when traveling backwards in a score – or in space. The musical relationships might sound different if a score is played backwards, but it doesn’t follow from this that they are not just the same relationships “in reverse.”

To be sure, we’re talking about a “virtual space” here. Notice that in most cases, some proportional scores notwithstanding, the literal spatial distribution of notes on the page does not have to correspond to score-positions. In a 4/4 measure with three quarter notes crammed into the left side of a measure and plenty of space between the third and fourth quarter notes, the distances in score-position are still equal. Yet virtual or not, score-position seems, in many respects, analogous to space and disanalogous to time.

But consider, we tend intuitively to think about beats and note values in two different ways. They can be thought of as a constant unit, e.g., the absolute size of everybody’s musical passage is 10 quarter notes, regardless of tempo. But they can also be thought of as relative units: in my tempo I play 10 quarter notes, but someone playing half as fast as me plays 20 quarter notes (10 half notes), relative to my tempo.

This is quite different from the way space behaves. A strange thing happens when we treat the length of a musical passage analogously to a distance in space. Because note values can be thought of as relative units, the size of a passage is tied to how fast it is played. If a passage of music is 10 quarters long at 𝅘𝅥 = 30 BPM, it is equal to 20 quarters relative to someone playing at 𝅘𝅥 = 60 BPM. If beats are analogous to spatial units, this would be like saying a distance traveled in space expands or contracts depending on the speed at which it’s traveled. Notice that this would not just be a conversion of units. It’s true that the total value of 10 quarter notes is equal to 20 8th notes in any tempo, just as 10 miles is equal to 20 half-miles at any speed, but this is completely independent of tempo or velocity. If I am traveling a distance of 60 miles at 60 mph it is not as though someone traveling at 30 mph is traveling 120 miles relative to my velocity. Rather, it is the time value that doubles: at 60 mph it takes 60 minutes, at 30 mph it takes 120 minutes. In this respect, beats, and thus score-position, are analogous to time and disanalogous to space.

In reality, beats and note values are merely a subdivision of time units. Since score-position is measured in beats, it is actually a temporal dimension. This is much more obvious when we consider musical styles and cultures that do not rely on scores. It is only because of the tendency in classical music to think of music in terms of objects, i.e., musical compositions visualized by scores, rather than as a dynamic activity, a temporal process, to wit, performance, that the spatial analogy comes about at all.

But if this is right, how can we explain the disanalogous relationship between time and score-position in those earlier examples? First, consider that we can always specify some fixed division of an arbitrary unit without specifying what units are to be divided. We can always say the size of a piece is a fixed number of divisions (e.g., 100 quarter notes) without specifying the time unit to be divided. Alternatively, we could say that the piece is e.g., 100 actions long, spaced equally in some time unit. To say that 100 quarter notes are to be played at 60 BPM is to say we are dividing a time unit (1 2/3 minutes) into 100 sections (100/60). On this view, tempo does not act like velocity in classical mechanics, which brings together two distinct parameters – space and time, it is rather a way of specifying the time units we’re dividing.

What about “backwards” or “upside-down” transformations of the score? To play a score “backwards” is simply to repeat a series of actions in a different (i.e., opposite) order in time. Note that the “upside-down” orientation is not really descriptive of score-position, it is a way of describing pitch relationships. Independently of pitch, to play a score “upside-down” is equivalent to playing it “backwards.” Note also that pitch, just like time or score direction is a 1-dimensional continuum; there are only two possible directions “up” and “down.” If we were to imagine a notation system that writes relative pitch in a horizontal orientation instead of vertically, we would see that “upside-down” pitch is just the same transformation of the continuum as “backward” score-position. It might be argued that pitch relationships are not themselves temporal. A chord might be simultaneous in time yet distributed across pitch. In this case pitch and time constitute legitimately distinct parameters, yet precisely because of this, the analogy to time dilation still fails: you can’t reduce the “time direction” of a musical passage by taking a longer or faster trip in the “pitch direction.” Time and pitch do not form a continuum. This is different from time and score-position. Time is indeed a continuum, but score-position is not a direction along that continuum, it is a way of dividing it.

What about time travel and its paradoxes? This is not really relevant to space and score-position. For one thing, since space does not have a “flow” one can’t travel “backwards” in space, except by convention. You can always say motion in one direction is “backwards” relative to motion in the opposite direction, but there is no fact of the matter as to which motion is really “forwards” or “backwards.” They are simply symmetrical. Obviously, the direction in which we play a score is also a matter of convention. But even if we grant that playing a score involves a correct direction, that no one, for instance, has ever played Beethoven’s 9th symphony backwards in its entirety, the lack of paradoxes associated with time travel is still irrelevant. Time travel paradoxes arise because of the nature of causality and its apparent “necessary time order”: causes seem necessarily to proceed their effects (or are at least simultaneous with them). But causality is not a feature of musical relationships, even though we often talk about them in causal language. We might say things like “the explosion of brass and percussion at the climax causes a dissipation of the musical energy that builds up prior to it.” But this is a metaphorical use of causal language. If we were to jumble up the order of events, we’d lose the causal analogy but there would be no logical paradox. Musical order is not necessary in the way causal order apparently is.

This is not to say that score-position, or what we might call beat-space, is not conceptually separable from time. For instance, we seem to have no problem thinking of a musical composition, and all of its musical relationships, as existing “all at once” independently of time, in a way that resembles space. If you doubt this, ask yourself whether you agree that Beethoven’s 9th Symphony exists even when no one is playing it. This conflicts with our intuitive picture of time. What does it mean to say every moment over, say, the last year exists “all at once?” Wouldn’t it simply be a contradiction to say that moments of time are independent of time? But it doesn’t follow from this that we are thinking of two separate domains – time and score-position or beat-space. Rather we are simply distinguishing two different ways of thinking about time itself. To think of a composition as existing “all at once” is to take an “external” or “eternalist” view on time, to render time in spatial terms. This is distinct from how time is experienced “internally” to the flow of time. This is directly related to the way we think about a musical work existing separately from its performances. To conceive of music as a collection of works is to take an external view on it. But to experience it in performance is to see it “from the inside.” There is some question about which perspective is more adequate to time. Is it a block existing outside of the “flow”, or is it a continuity to be grasped internally to the flow itself? This question is at the heart of the philosophy of time from Augustine to McTaggart to Einstein, Bergson and beyond.

Returning to the special theory of relativity (STR), we can see that the geometry of Lorentz transformations requires spacetime to be continuous, rather than discrete, or grid-like. This is one thing Bergson gets wrong about the theory, but luckily for him, it makes it compatible with his own philosophy. In STR the speed of light in a vacuum is constant across all frames. The only way to keep this invariant is through Lorentz transformations. If spacetime were discrete, the time coordinates in any given inertial frame would have to be evenly spaced ticks, i.e., integer multiples of some basic unit (even if that unit is extremely small, or itself an irrational value). But when you move to another frame, the Lorentz transformation smears space and time coordinates; part of one frame’s space becomes part of another frame’s time. The new coordinates are related to the old ones by a hyperbolic rotation.

Now, here’s the problem. The angle of rotation – technically, the rapidity (𝜙) – between two arbitrary inertial frames (the amount that space and time mix) can be any real number (𝜙 ∈ ℝ), not just a whole number. In fact, the transformation ratio is usually irrational (like n/𝜋). This means that the time coordinates along the same worldline, when expressed in different frames, are stretched or contracted by factors that are typically irrational or even transcendental multiples of one another. And so, the proper time intervals along that worldline (which are frame-invariant, remember) can’t coincide with evenly spaced grid points in every frame. The proper time of the worldline won’t be discrete across all frames. Yet, by definition, it is invariant across all frames, so we have a contradiction. Spacetime can’t be discrete; it must be continuous.

If spacetime were discrete, events could only occur at discrete coordinate values in every frame. But then it would be impossible for one-and-the-same invariant proper time to be a multiple of the fundamental unit in every frame. Since proper time is continuous and invariant across frames, and since discrete grids between some frames are incommensurable (their spacings don’t rationally align under arbitrary transformations), it follows that the only consistent possibility is for spacetime itself to be continuous. In addition, if spacetime were discrete, this fact would be captured by some frames but not others and so there would be privileged frames (some frames get it right, others distort it). But if this were the case then proper time would also lose its frame-invariance.

A MATHEMATICAL CODA

For those of you interested in the math here, check out these equations (they’re not so difficult). First let’s define Galilean transformations to see why they work at non-relativistic speeds. Then we’ll see what changes in the Lorentz transformation. Let’s take two reference frames, each of which assigns a spatial coordinate, x and x′. Each frame defines its own spatial origin: x = 0 for the first frame, x′ = 0 for the second. The origin of the x′ frame moves at a constant velocity (v) relative to the x frame along the x-axis. Time is the same in both frames (t = t′). The Galilean transformation relating their spatial coordinates is (x' = x - vt). Solving for x gives (x = x' + vt). This reflects the fact that each frame describes the other as moving with the same speed but in the opposite direction. For example, from the perspective of the x-frame, if the x′-frame is on a train moving east at 300 mph, then after one hour the origin of the x′-frame is at x = +300 miles (x = 0 + (300 x 1)). From the perspective of the x′-frame, the origin of the x-frame is at x′ = −300 miles after the same hour (x’ = 0 – (300 x 1)). In our musical analogy, (v) is the tempo differential (e.g., 60 BPM – 30 BPM = 30 = v), (t) is time, and (x, x’) are positions in the score after some time (t) has elapsed.

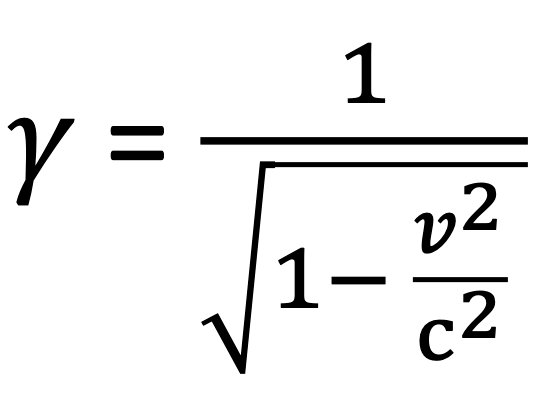

Remember, the Galilean transformation assumes one universal time (t = t’) and no speed limit. But the Lorentz transformation assumes one universal speed limit (c) and time must adjust to preserve it. Space and time mix. The values of x and x’ simply need to be scaled by a Lorentz factor (𝛾). But time is not constant across frames: t ≠ t’, so we have to account for the differences in time between frames. This gives us x' = 𝛾(x - vt) and x = 𝛾(x' + vt).

The Lorentz factor is

So, the Lorentz transformations of x and x’ would be

for t and t’ we get

One thing about c²: it’s a really big number; c is roughly equal to 3 x 10⁸ m/s, so c² ≈ 9 x 10¹⁶ m²/s².* The fastest recorded crewed airspeed is c. 28,000 km/h (approximately 7800 m/s) during the STS-2 mission of the Columbia orbiter in 1981. Squaring this would give us v² ≈ 6 x 10⁷ m²/s². So, the decimal value of v²/c² in this case would be just 0.00000000066…(6.6 x 10⁻¹⁰). Subtracting this from 1 gives us a value that is so close to 1 that the difference is negligible (but not absent). This is why the Galilean transformation works, up to a “rounding error”, for even the fastest speeds that we are currently capable of traveling at. The same goes for the time conversion. If the ratio of vx/c² ≪ 1, (i.e., if it is very close to 0), then t’ ≈ 𝛾(t – 0), and since the Lorentz factor here would be 𝛾 ≈ 1/√(1 – 0) ≈ 1, we get (t’ = t). However, if we boost to 2.97 x 10⁸ m/s (0.99c), we’ll get a Lorentz factor of 𝛾 ≈ 7.09. If x = 0 and t = 1h (3600s) that gives us

t’ ≈ 7.09(3600 – 0) ≈ 25,524s ≈ 7h 5m.

So, an hour in the frame with a fast velocity dilates to over 7 hours in the rest frame. If we could travel at lightspeed, time would dilate infinitely relative to all rest frames. You might ask, “how would it appear from the point of view of lightspeed?” However, this question has no answer; there is no “point of view” from lightspeed. In STR the equations for transforming one velocity’s “point of view” to another’s are all based, once again, on the Lorentz factor:

Notice what happens if a frame’s velocity is equal to lightspeed (v = c): we end up dividing by 0! Since velocity can be any real number less than c, an object’s velocity can infinitely approach lightspeed but can never reach it.

Empirically, light never slows down or speeds up when measured from different frames. A lightspeed frame would require the light to be at rest relative to itself, where rest means v = 0, but this conflicts with the defining empirical fact that light always moves at the same speed for every possible observer. So, a frame where v = c would require light both to move and not to move at the same time, which is physically and logically impossible.

*Squaring a velocity (m/s) effectively converts it to an energy-per-mass quantity (m²/s²). It tells us how much, and over what distance or time, we have to accelerate in the opposite direction to stop moving. It determines the spatial distance we would continue to travel in the same direction despite accelerating at some rate in the opposite direction. It basically tells us how much forward motion needs to be “paid off.”